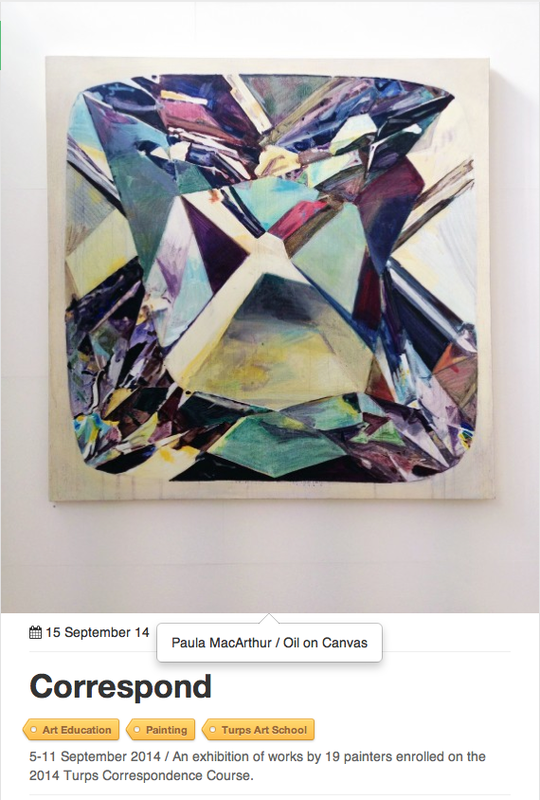

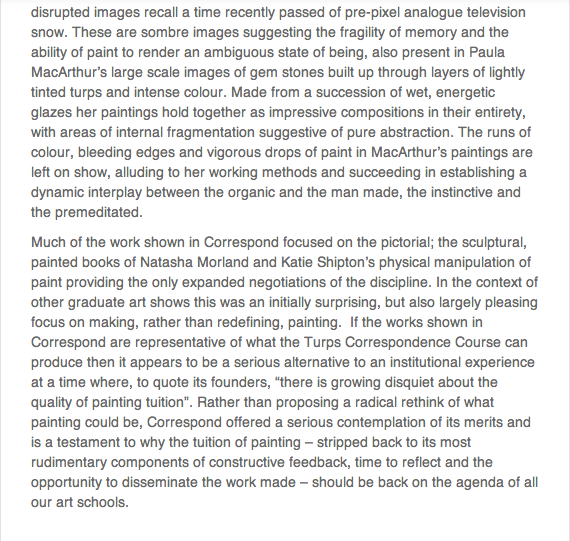

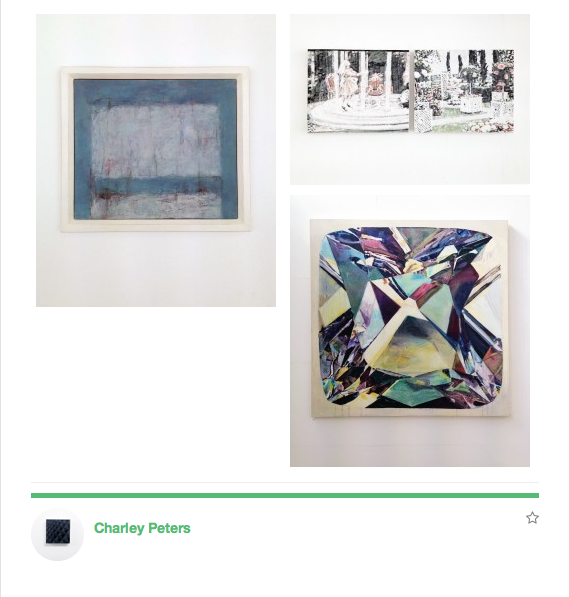

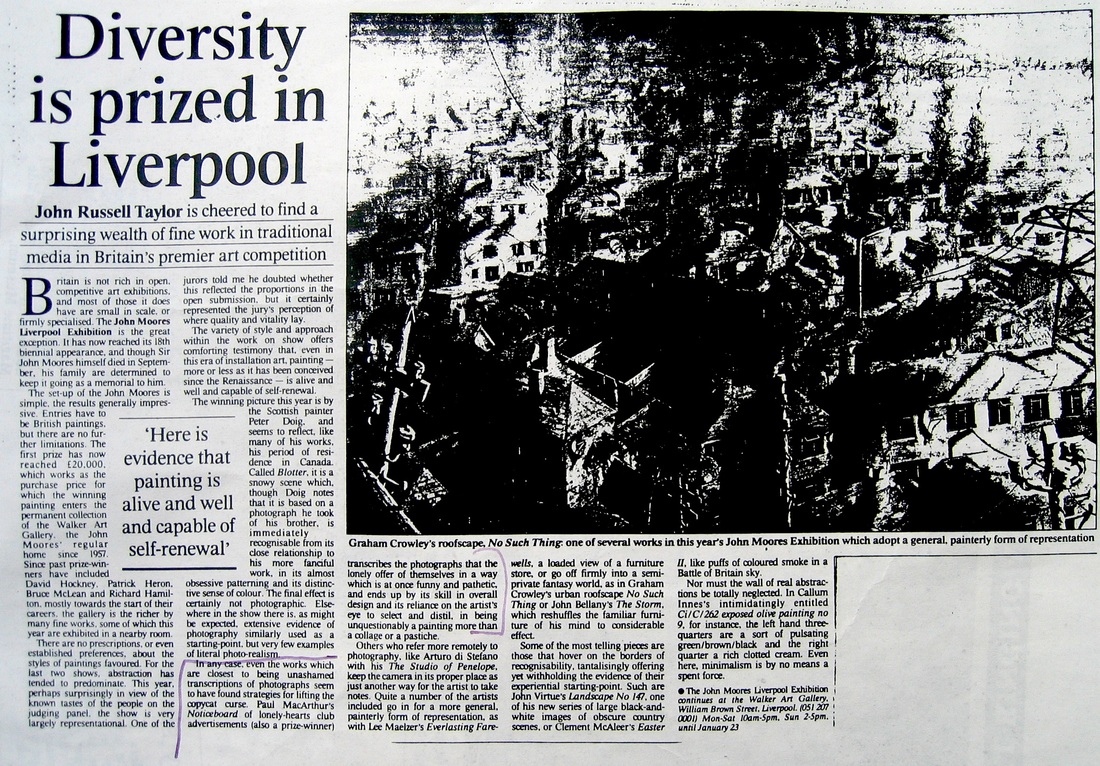

Paula MacArthur: Infinitely Precious Things 60 Threadneedle Street, London EC2R 8HP 24 January - 9 May 2014 Reviewed by: Anna McNay » Thick, vibrant, brightly coloured, viscous paint, sparkling, shimmering and reflecting light, both from its surface and from its subject. Like from pools of oil, or petrol in a puddle, thousands of tiny rainbows are refracted. Suns and stars, burning and emitting heat, bright against the night sky. Yet the threat of meltdown looms, fragility and ethereality, drops of water amidst the oil causing it to disperse. We’re in the heart of the City and looking at a giant heart-shaped diamond – the centenary diamond – on an immense 2x3 metre canvas. Let Me Hear You Say The Words I Want To Hear. It’s a new work by award winning painter Paula MacArthur (she won the John Player Portrait Award – now the BP Portrait Award – before even finishing her foundation course and later also won a prize in the John Moores competition). Originally a portrait painter, MacArthur has been working with gemstones for a couple of years now, since a visit to the collection at the Natural History Museum for her 15th (crystal) wedding anniversary. Inspired, she painted a watercolour of 15 stones from found images, and, from there, from the initial romantic personal gesture, things grew. Literally. Speaking of her large-scale canvases, MacArthur says: ‘It suddenly felt that that was the size they needed to be. The scale worked for me, with the size of the brush marks.’ Indeed, it is about brush marks and painterly gesture, as much as it is about romance, and as much as it is about precision. There are two stages to MacArthur’s travails. First, she spends time flicking through images – all of the gemstones in the Natural History Museum collection are photographed – and then, every so often, one will catch her eye. Working with her own photograph, she then ‘messes about’ on photoshop. Often there are elements in the photograph which don’t really belong – floating highlights in the background or flaring effects – ‘I’m not a great photographer,’ she confesses, and ‘they’re very difficult things to photograph because the light changes in a millisecond.’ But each of these elements adds something to the overall composition. Next, it’s a question of colour. Here, MacArthur becomes excited: ‘It’s the colour that’s the important thing for me in the first place and I just want to ramp it up. These are excessive objects on so many different levels, that’s just saying “More!” really. It’s always the colour that’s the hook.’ And so she puts the colour slider up to 100% saturation – and continues to exaggerate the colour throughout the process, in the painting too, by mixing in lots of linseed oil to make it really rich. Once the design part has been completed – a process which takes about a day – MacArthur flips into a different mode and is ready to begin to paint. ‘[Now] it is about constructing it, it is about the craft, it is about enjoying the process. It becomes quite spontaneous and instinctive and kind of meditative.’ Working with an A4 printed image, she uses an overhead projector to lightly draw an outline of the gemstone on the canvas – ‘because they do need to be symmetrical’. Nevertheless, the projector distorts, and so she ends up redrawing quite a lot as she works through. The facets of the stone become like a grid and MacArthur treats each facet like a little painting in its own right, as she works systematically across the canvas, thinking about layers of colour. Cyan, magenta, yellow and key. A recent foray into screen printing has led her to think much more in these terms. Her three most recent works – Now And Forever Until The End Of Time, Let Me Hear You Say The Words I Want To Hear and Who’s To Say That I’m Unhappy –produced since she found out she’d be showing at 60 Threadneedle Street back in September, all use a lot of fluorescent pink. This, MacArthur had to mix herself, since you can’t buy fluorescent oil paint. ‘It looks like icing sugar!’ she says. ‘It makes your eyes hurt! It’s fantastic stuff!’ What she likes best is that the undiluted colour has spilled round on to the edges of the canvases, from where it reflects on to the wall, giving a neon glow – or halo – around the works. And then there are the drips. These came about after MacArthur took an extended break from painting to get married and have children. Having begun her career as something of a purist, trained at the Royal Academy and described even by Brian Sewell (in an otherwise positive review of her John Player Portrait Award portrait) as ‘irredeemably brown’, MacArthur began, in the early 2000s, a series of Memphis works – ‘lots of Americana, basically.’ She was working on a large painting of Elvis Presley’s favourite gun – again, all about excess – when, before leaving her studio one day, she painted the background red. When she came back the next morning, the whole thing had slipped on to the floor. ‘It looked like there’d been a murder!’ Wanting it really glossy, she’d added lots of linseed oil and turps – clearly too much for the canvas to hold. But, amidst the mess, what was left behind was a magenta glaze which MacArthur really liked, and so she started to experiment. ‘It’s a dangerous thing,’ she says, ‘because it can start to look quite contrived. It’s a fine line as to what you allow.’ In Let Me Hear You Say The Words I Want To Hear, for example, lots of the drips have been painted out. ‘It becomes quite fragile with the drips and sliding paint,’ MacArthur continues. ‘It seems aggressive, but it’s also fragile – quite a nice metaphor for a relationship, in fact, something which could just slip away. It is all about relationships and love, really, and what that represents. But there are so many different layers of association with gemstones that I am also feeding on.’ These include wealth and capitalism, which become especially relevant when the works are being shown in the city. On the surface, from afar, the stones look valuable and perfect, but on closer inspection, maybe there is a fracture or a scratch. Similarly, with MacArthur’s paintings, from a distance, they can look almost photorealistic, but, as you move closer, they become something completely abstract. The focus moves from the gemstone to the physicality of the paint. ‘I think the paintings invite you to come and look at the surface. But, as you try to approach them and attain them, it all just disintegrates, and it becomes what it really is – the paint and the marks. And I really enjoy that.’ Metaphorically, it’s just taking something – a jewel or a relationship – and putting it under a magnifying glass. Hence the role of the questioning titles, all except for one of which are lyrics from love songs (the exception being Of Course I Still Love You which is the name of an Iain Banks spaceship). In Everything I’ve Had But Couldn’t Keep, for example, the drips and rivulets, the streaks of light, rather reminiscent of a Klimt painting, really fit the title, reflecting the idea of everything just slipping, sliding and melting away. Tell Me Love Is Real – a bright orange twinkling sun – takes its name from a lyric in the song to which MacArthur had her first dance at her wedding. Even this, however, is an insecure, questioning statement. ‘They’re about my deep seated insecurity,’ says MacArthur, referring both to the titles and the works themselves. ‘But I think everyone struggles with that. They’re about the strength of passion against that fragility and neediness. Hopefully some of that comes through the paint. They’re quite big and bold and in your face. Loud and proud. But, actually, they’re quite delicate. They’re tiny things.’ Metaphor and reality melt together, just like the paint, oil and glistening reflections. MacArthur herself has said it all – these works are loud and proud, almost photorealistic, stunningly so, wealth and splendour writ large. But they invite you in, at which point they disintegrate, become abstract, become about the paint, and then, as you move yet closer, they become about so much more – the titles, the inspirations, the hopes and fears and insecurities which plague us all. Such a tiny exquisite and valuable gemstone, magnified and shown large-scale with all its flaws, reflecting back the innermost facets of the artist and of the viewer. Anna McNay Art writer and researcher based in London. sites.google.com/site/annamcnay/ Venue detail: 60 Threadneedle Street, London EC2R 8HP  STILL LIGHT The Luminous Paintings of Paula MacArthur "Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass, Stains the white radiance of eternity, Until Death tramples it to fragments." Adonais by Percy Bysshe Shelley written upon the death of John Keats in 1821. Paula MacArthur's paintings are a testimony to the primacy of vision. Light is not only the subject matter and content of Paula MacArthur's luminous and rather exquisite paintings but it's also their medium. Paula's paintings draw us into the now. For most of us; light can be many things, but for Paula; it's a celebration of the senses and an affirmation of values. This isn't simply a celebration of light but of life. The key to this sort of achievement is transformation. This is one of the principle elements that distinguish painting from illustration. This is the transformation from paint into light and space. A kind of latter day alchemy. Paula's paintings demonstrate that to paint about love - you have to paint lovingly; otherwise simply depicting acts of tenderness becomes illustration. It's no coincidence that Paula employs a method that eschews easy and mannered expressionistic rhetoric. Her recent work is closer in method to the meticulous paintings of Chuck Close. For her a sense of precision is essential. Light not only functions as space in painting but it can also lend the painting, what has been described as 'air'. Air in this context is the imagined space in which events 'unfold'. This is space as light and light as space. This is pictorial space; indeterminate and fictitious. This is the legacy of cubism. Paula also employs reflection and refraction to compress several shattered and partial spaces into one fictitious 'event'. Diamonds are complex and contradictory objects. There are few artefacts that are as demonised and fetishised as diamonds. Fewer still are as intimately bound to ideas of transformation and energy. The list of diamond's distant and not-so-distant 'cousins' is impressive. Whether it be a life forms like us; a sack of coal or a stick of graphite. Diamonds represent a massive contradiction and like fire, they have the potential to be both fascinating and dangerous. Simultaneously beguiling and deadly. Love over gold - Don Van Vliet Whenever I look at images of diamonds, I can't help but think about issues of affluence and poverty. Hatton Garden is a street distinguished only by security grills and litter; very Basildon. There's also the constant round of tabloid representations of Knightsbridge for the hard of thinking. And there's the rather tawdry dystopia that is reality TV. Shows which are epitomised by ITV2's 'The Only Way is Essex' , which for those of you who've been trapped in Antarctica recently, features talkative, narcissistic twenty-somethings banging on about shopping. They appear affluent and oblivious. Theirs is a celebration of conspicuous consumption. The wider world doesn't exist. The Edward Snowdens of this world need not apply. In 1960 Roy Lichtenstein painted 'The Ring'. Lichtenstein based his painting on a black and white advert for a 'budget' diamond engagement ring, so we mustn't loose sight of the fact that he didn't subsequently paint a diamond ring. He painted an image of an advertisement for an engagement ring, which is a very different matter. This is subsequently reflected in the work of Gerhard Richter. In Richter's paintings its the photograph rather than the image that is the subject. Second order meaning. The epitome of this culture of representation and misrepresentation has to be the rather creepy adverts for the diamond mining company de Beers. These adverts hark back to the world of Ian Fleming and James Bond. A world of second rate fiction. There's no mention of the 'taint' that colours the reputation of diamonds. In the 1960's Liz Taylor and Richard Burton's shopping trips kept tabloid newspapers supplied with anecdotes which invariably involved pornographic descriptions of a 'million dollar diamond'. Then there's the nightmare world of child soldiers and 'blood' diamonds. It's almost impossible to regard diamonds in an aesthetic or aspirational manner without appearing to have amnesia. Light is synonymous with life. Which is probably why we take it for granted and why trying to comprehend light is almost impossible. It's rather like asking a fish what they think of water. Or more absurdly; whether they 'like' it. "I'd rather have roses on my table, than diamonds round my neck" - Emma Goldman When I think of light and luminosity, I'm overcome by a sense of well-being. Something like happiness. In the same moment I begin to visualise Newton et al, at the height of the enlightenment, experimenting with prisms and mirrors. Splitting light; even the expression sounds heroic. Paula's is a new world of reflection and refraction. Not for her the lazy and rhetorical conventions of expressionism. As they now seem dated and absurd. Luminosity in painting is invariably absent from spontaneous or expressionistic painting. This is because painting in an expressionistic manner can't accommodate the rather systemic method of painting necessary to construct luminosity and transparency. For a painting to be luminous the pigment has to be suspended or partially dispersed, not saturated. This can only be undertaken in a considered and methodical manner. Even using white becomes problematic. "I'm a dirt person. I trust the dirt. I don't trust diamonds and gold" - Eartha Kitt The paintings of Paula MacArthur depict cut diamonds; but in such a manner that they appear to employ a cubist space. Paula's method of depiction relies upon transparency and indeterminacy; both apparent and poetic. This is close to the idea of the 'crazy diamond'* that Pink Floyd sang about. The idea of 'shining on' being synonymous with inspiration and vision. Paula's paintings embrace and celebrate the 'primacy of vision'. For too long painters have allowed narrators to 'account' for their work. Paula's subject matter is also a vehicle for content which is light - relayed through light. Aldous Huxley in one of his many essays draws a striking parallel between the cutting and finishing of gem stones and the potential of painting to 'split light'. He singles these two activities out as they both (in the right hands) seem to be able to 'fashion' nature - or more correctly light. This is what Suzi Gablik would later refer to in her 1995 book as the re- enchantment of art. For Paula this has meant employing characteristics that are intrinsically painterly and unique to painting. Something that would, I'm sure, have earned Clement Greenberg's1 approval. "Remember when you were young, you shone like the sun, Shine on you crazy diamond. Now there's that look in your eyes, like black holes in the sky. Shine on you crazy diamond." - Pink Floyd If Huxley had lived longer he might have added the cathode ray tube, television and the computer screen. Luminosity isn't the same thing as bright or colourful. It's about energy and life. The kind of life we occasionally glimpse in direct sunlight and the kind of light we can imagine. The 'light at the end of the tunnel' as 'Half Man, Half Biscuit' claim turns out to be the light of an oncoming train that'll eventually maim and kill you. Luminosity is the sense that an object is a source of light not merely a reflector. Most paintings until the mid/late 19th century appeared to exude light. Modernism's focus upon the 'thing itself' meant that many established aspects of painting had come to be regarded as limitations and as such were cast aside. Luminosity was such a casualty. "Poetry is indispensable - if only I knew what it was for" - Jean Cocteau. In Rembrandt's 'Night Watch' what appears to be Rembrandt's wife Saskia strides across the centre of the painting from left to right. She illuminates her surroundings. it's as if she has become a 'beacon'. She is the militia's inspiration. This is a painting in which light not only reveals and depicts, but is also symbolic. The 'Night Watch' represents nothing less than the birth of a nation. The 'Night Watch' is established as a national monument; an icon. Up there with the Eiffel Tower, the clock tower of Big Ben and the Statue of Liberty. The fact that light is held in awe is self-evident. Without it life would not only be inconceivable but untenable. Light features in almost all religions and broadly signifies some aspect of deity or godhead. It was Jesus Christ who famously said 'I am the light of the world'. In a more secular world light is also associated with health and happiness; radiance. From the sheen of something freshly polished to the blinding light of a nuclear explosion. Pure energy. Existence is often referred to as “a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” 3 "The light that work sheds is a beautiful light, which, however, only shines with real beauty if it is illuminated by yet another light" - Ludwig Wittgenstein It's become a nostalgic fallacy to regard art as a liberal, humanist project. It's a market - pure and simple as markets are without morality. During the last twenty years the art market has become ubiquitous . The art market like any market is without morality. It feeds a toxic mix of capital, celebrity and media. Paula's paintings act as a simile and draw our attention to the art market as a 'diamond mine' What lingers after seeing these extraordinary, luminous paintings is a sense of joy. This is a celebration of light, life and love. Graham Crowley - London - 2014. Bibliography: 'The image in Form' - Collected writings of Adrian Stokes - Edited by Richard Wollheim - 1972. 'Ends and Means' - Aldous Huxley - 1937. 'Culture and Value' - Ludwig Wittgenstein - 1977. Published posthumously. 'The Necessity of Art' - Ernst Fischer - 1959. 'The Psychoanalysis of Fire' - Gaston Bachelard - 1938. 'The Poetics of Space' - Gaston Bachelard - 1958. 'The Reenchantment of Art' - Suzi Gablik - 1995. 1 'Art and Culture' - Clement Greenberg - 1961. 2 'Shine On You Crazy Diamond' - Pink Floyd - 1975. Tribute to Syd Barrett. 3 ‘Speak, Memory’- Vladimir Nabokov |

Paula MacArthurPainter Archives

October 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed